Glimpses of Healing and Hope

July 4, 2016

by: Jane Bishop Halteman

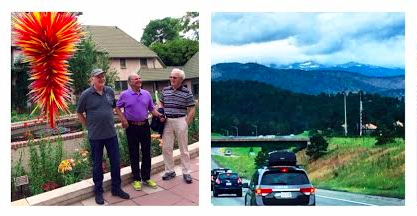

Jim and my brothers at Denver Botanic Gardens; driving to the mountains

I’ve traveled in and out of Denver a number of times, both as a meeting planner decades ago and to visit my brothers’ families over the years, so I’m not a stranger to spending short periods of time at mile-high altitudes.

During a trip to visit family in Colorado this last week, I began noticing the change in the atmosphere as we made our way between Denver and higher altitudes in Cordillera. A little more breathless than usual on the stairs and feeling more intensely the ups and downs of the walking path on the par-three golf course, I began to research more carefully how to navigate the switch between altitudes.

An article entitled Ten Non-medicated Ways to Cope with Altitude suggested that hydrating, eating regularly, slowing one’s pace, and acclimatizing go a long way toward preventing or overcoming altitude sickness. As I read through the recommendations to keep altitude illness at bay, I couldn’t help but notice similarities to healthy practices for the ascents and descents in life.

Consider the ways you are aware of life’s ups and downs as holy ground as you examine these four directives to ensure you are breathing well in high altitudes. What likenesses and differences do you see between good spiritual practices and managing a change in altitude well?

Stay thoroughly hydrated:

“Always stay thoroughly hydrated on any hike, but particularly those involving travel above 7,000 feet elevation….Drink before you get thirsty, as thirst usually occurs only after you are already dehydrated. This means try to drink at least six to eight ounces every 30 to 45 minutes on hot summer days when you are going uphill carrying a heavy pack.”

A second source offers this about the importance of adequate hydration:

Staying hydrated is “the best way to help your body adjust to high altitude. Generally the low humidity at altitude keeps the air dry, so you should drink twice as much water as you would at home. Also keep in mind that you want to add water to your body, not deplete it. At least initially, avoid caffeine and alcohol.”

Eat regularly:

“Whether you feel like it or not, you must keep eating. Your body works hard to go uphill and carry extra weight; if you are traveling at altitude the stresses on your body are even greater and you probably will feel less interested in food. Be sure to test snack and meal food ahead of time at sea level and only take with you whatever is palatable and satisfying down low, minus spicy or hard-to-chew foods. Include carbohydrate solutions to add to your beverages….Have some hard candy, jelly beans, lemon drops handy so you have ready access to your main fuel source: carbohydrates.”

Slow your pace:

“In order to enable you to continue steadily, listen carefully to your body and be sure to start out a little slower than you normally go to warm up well and hit your stride. If you try to push it to keep up with the fastest member of your party you may not make it to your goal. In the case of altitude climbing, the tortoise usually outpaces the hare in the long run, but the key is to go at a slow and steady pace.”

Acclimatize:

“This isn’t just a technical term mountain climbers throw around to sound cool. Adjusting to higher altitude can take a few days. If you have the time, consider spending a night or two at an intermediate altitude. If that’s not an option, plan calmer activities the first 24 to 48 hours of your trip.”

Another source suggests that “foods rich in potassium are great for acclimating. Some good staples to eat include broccoli, bananas, avocado, cantaloupe, celery, greens, bran, chocolate, granola, dates, dried fruit, potatos, and tomatoes. Do your body a favor and decrease salt intake. Additionally, complex carbohydrates are great for stabilizing your blood sugar and maintaining energy. Eat plenty of whole grains, pasta, fruits, and vegetables.”

This last week’s experience in the Rocky Mountains reminds me of the Sherpa guides from Tibet and Nepal, “famous for the remarkable assistance they provide to Himalayan mountaineering expeditions. These mountain guides are hardy, experienced, and skilled. They know the joys and dangers of the ascent and descent. They have come to an understanding of the terrain, its beauty, and its risks. They know where there are hazardous and slippery paths. They watch out for the signs of altitude sickness in the climbers. They walk beside the explorer and help to carry the load and share the burden. Sherpas are keenly aware that they tread on sacred ground: the mountain is a holy place, not to be 'conquered,' but to be approached with awe and respect.” (From Andrew D. Mayes’ Learning the Language of the Soul: A Spiritual Lexicon)

With what do you hydrate your spiritual life? What do you feed upon to enhance the journey? How do you slow your pace in order to pay attention to what’s most important? Have you found ways to acclimate to new goals and practices? Who has functioned for you as a Sherpa? For whom have you offered the loving care a Sherpa makes available to a climber?